According to Adler, the individual is socially embedded. Every sane philosopher, who has ability of judgment, should insist that the human beings are social existence. If we assume that the individual is not social, we cannot prove the inevitability of the morality. Therefore, this is assumptio non probata, fallacy of assuming the point in debate. Anyway, the individual is socially embedded, as far as we want to talk about the morality.

There are two aspects of the “embeddedness”; i.e. spatial and temporal.

Adler said [1]:

This social feeling remains throughout life, changed, colored, circumscribed in some cases, enlarged and broadened in others, until it touches not only the members of his immediate family, but also his extended family, his nation, and finally, the whole humanity. It may also extend beyond these boundaries and express itself toward animals, plants, lifeless objects, and finally toward the whole cosmos.

In this context, the social embeddedness is understood from the spatial aspect. An individual is contained in the present family, the family in a present nation, and the nation in the present humanity. He does not mention the history of the family or the nation.

In another place, Adler said [2]:

We find all the previous useful contributions which have been supplied by our forebears. We find human beings in their bodily and mental development, social institutions, art, science, lasting traditions, social relations, values, schooling, etc. We receive all these and build upon them, advancing, improving, and changing, always in the sense of a further durability. This is the inheritance from our forebears which falls to us for administration.

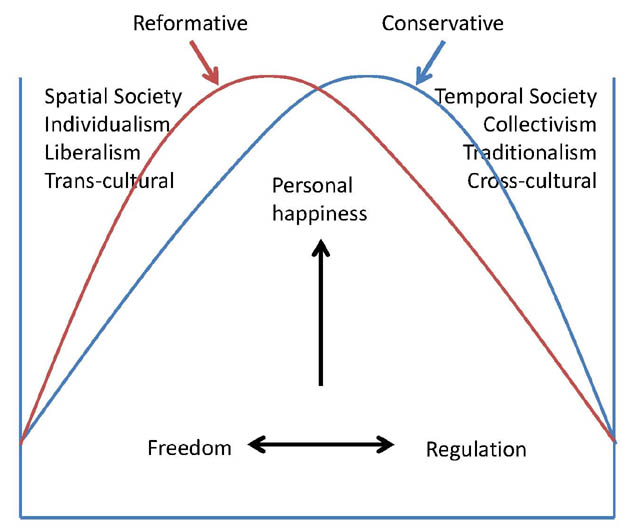

Here he pointed out the temporal aspect of the embeddedness. An individual is understood in the history of the family or the nation. These two viewpoints are somewhat contradictory in the history of moral science.

If we consider an individual in the spatial society without thinking its history, we can argue based on the belief on reason without taking tradition into account. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, a French philosopher, did this in his “Emile” [3]:

The only man who follows his own will is he who has no need to put another man’s arms at the end of his own. From this it follows that the greatest good is not authority but freedom. The truly free man wants only what he can do and does what he pleases. This is my fundamental maxim. Apply it to childhood, and all the rules of education spring from it.

He stood against all the tradition of France, and tried to build up a new education system based on reason. Not only Rousseau but also many philosophers in the enlightened era adopted the spatial connotation of the society. It is perhaps influenced by modern science that was essentially synchronic and tried to explain changing things from non-changing elements and principles. This trend of thought is inherited in modern liberalism. The extreme liberalism, which denies all the history and tradition, often falls into anarchism. For example, Japan Teachers’ Union, which is effected by radical liberalism, insists that the moral education infringes children’s freedom of thought.

When we consider an individual in the temporal society, i.e. in the history, we necessarily become traditional and conservative. Johann Gottlieb Fichte, a German philosopher, wrote in his “Addresses to the German Nation” [4]

There comes a solemn appeal to you from your descendants not yet born. “You boast of your fore fathers,” they cry to you, “and link yourselves with pride to a noble line. Take care that the chain does not break off with you; see to it that we, too, may boast of you and use you as an unsullied link to connect ourselves with the same illustrious line.”

He actually gave this lecture under the occupation of France. Here he declares objection to Rousseau. His argument, however, is easy to be utilized by the extreme conservatives. Actually, this article was often quoted before the Greater Asia War in Japan to defend nationalism. It is apt to limit human freedom more than necessity.

Was Adler a reformative or a conservative? There is a controversy. Every Adlerian is setting his/her position in somewhere in the midst. Someone is rather reformative, while some other is rather conservative. I was rather reformative when I was young, and now I am rather conservative. Adler was the same; the first paper, which is rather liberal, was written in 1926 at 56 years old, and the second one, which is relatively conservative, was in 1933 at 63. I do not want to insist that my position is the only proper standpoint. There are wide varieties of interpretation for Adler’s opinion. Anyway, the truth is in the midst, not in the extreme.

[1] Adler, Alfred: Understanding Human Nature, translated by Colin Brett. Hazelden, Center City, Minnesota, 1998 (original 1927), p.35.

[2] Adler, Alfred: “The Progress of Mankind”, in Superiority and Social Interest. Norton, New York, 1964 (original 1933), p.26.

[3] Rousseau, J-J.: Emile, ou l’education translated by Grace Roosevelt, (http://www.ilt.columbia.edu/pedagogies/rousseau/Contents2.html).

[4] Fichte, J.G.: Addresses to the German Nation, translated by R.F Jones and G.H. Turnbull, (http://www.archive.org/stream/addressestothege00fichuoft/addressestothege00fichuoft_djvu.txt)