There is a Shinto shrine in my neighborhood. In the garden of the shrine, there are many plum trees. Recently the flowers bloomed. When plum flowers bloom, the Japanese feel the spring is near. The song of the bush warbler (Cettia diphone), a bird like a nightingale, is also a symbol of the early spring. Anglers are pleased to find the spring when they fish mebaru, a sort of rockfish (Sebastes). Anyway, March is the season which people like most.

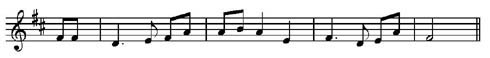

Japan has a lot of songs of the spring. When I was a primary schoolchild, I learned a song called “Haru no Ogawa” (A Brook of the Spring) at school. It was published in 1912 on the school songbook. When I sang it, my father said, “You got a wrong text.” He sang the song for me. His text was in the written language, but my text was in the spoken language. The meaning was the same. I said to him, “But, Father, I learned it in this way at school.” He said, “Show me the songbook.” I show it to him. He said, “Shit! MacArthur has taken away from us even child songs.” Click the score, and you can hear the music.

Before the war, official documents, e.g., the law, were published in the written language, and unofficial ones, e.g., newspapers and novels, were in the spoken language. The written language is a language of the Middle Ages, and is considerably different from the modern language. It is a beautiful language strongly influenced by Chinese, and can express things very briefly. Before the Greater East Asia War, texts of school songs were often written in the written language. When the War was over, GHQ/SCAP (General Headquarters/ Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers) ordered that all documents should be written in the spoken language. The Japanese Government obeyed the order, and the written language was not taught at school any more. As a consequence, many songs disappeared from the classroom. This song fortunately survived because the text was revised into the spoken language.

However, these old songs gradually disappeared from the school songbook, and, at last, in 2002, the Ministry of Education decided to delete all the old songs from the curriculum. I introduce another song of the spring which has disappeared from school. This is called “Oboro Zukiyo” (A Spring Moonlit Night). It is published in 1914. The text was written in the written language, but, as it was easy to understand, the song survived after the War.

The Japanese who are elder than 30 years old can sing these songs, but who are younger may not know them. At ICASSI in Gyöl, I was deeply impressed when Hungarian participants sang some child songs together. The Japanese have already lost such songs common to the young and the old. I believe it is necessary to have common songs to establish the national identity. George Kennan, an American historian, criticized in his book that General MacArthur was going to let communists take over Japan[1]. Actually, after MacArthur left, socialists and communists denied Japanese traditions to destroy the national identity of people. Even the Ministry of Education is polluted by anit-nationalism, and school songs are the victim of those destructive philosophies.

[1] George Kennan: American Diplomacy, 1900-1950. University of Chicago Press, 1951.